Click on the banner to read the full series in portuguese, english and spanish

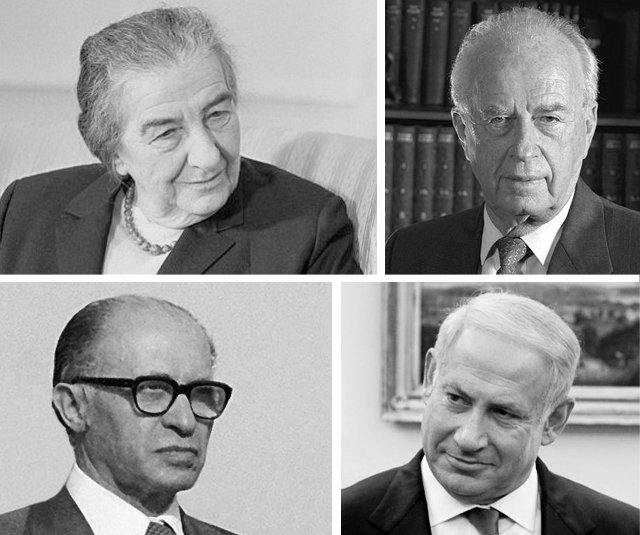

During the first thirty years of the existence of the State of Israel, the Labour Party and its allies were the country’s driving force. David Ben-Gurion, Moshe Sharett, Levi Eshkol, Yigal Allon, Golda Meir, Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres dominated the political scene, ahead of center-left Zionist governments.

Read more:

Israel: ethnic and social pressure puts democracy at stake

Army and religion influence politics in Israel

The historical origin of Havoda (the Hebrew name of this political stream) dates back to ancient Mapai, founded in 1930, which provided the main leaders for the Zionist movement, for the Haganah (its military wing) and for the independence war. Aligned with social democracy, it always attracted to its side smaller parties, both left and right-winged, which didn´t mind defending its program, centered on building an economy based largely on cooperatives and on public property.

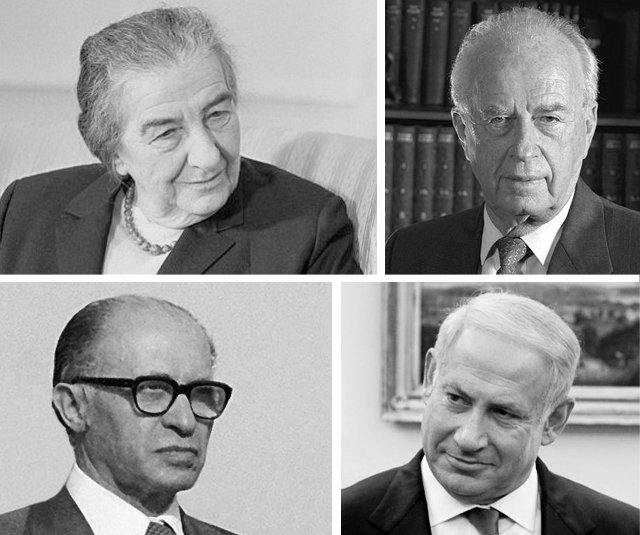

Montagem/Wikicommons

Clockwise former prime ministers Shimon Peres, Benjamin Netanyahu (the third administration), Yitzhak Rabin and Golda Meir

The Labour Party’s voting base was made of the earlier generations of immigrants coming from Central and Eastern Europe, called Ashkenazi. This slice of Judaism commanded major collective farms (kibbutzim), the military, trade unions and the cultural life. For some decades, they were the majority of the Israeli population.

New immigration flows, however, altered the demographic composition and helped undermining the dominance of Ben-Gurion’s followers, according to many studies. Jewish waves of immigrants coming from North Africa and other Middle Eastern countries, the so-called Sephardim, put pressure on the system organized by the previous European immigrants.

In addition to these groups, between the 70’s and 90’s, a wave of refugees from the Soviet Union and other socialist countries was added. Over one million Russians, for example, came during that period. Most were very critical of any idea that even smelled of socialism and were eager to show the best and most Orthodox Jewish credentials.

Above all, these Sephardic and neo-Ashkenazi segments were poor and felt they had fewer opportunities than the traditional social strata of Israel. They were ready for a message that would open new roads for them and clearly defend their interests. Those were, ultimately, the right conditions for the rise of the Zionist right, which adjusted its speech to the dynamics of these social actors.

The Likud’s victory

It was in this scenario that the Likud won the 1977 elections, with Menachem Begin becoming the prime minister until 1983. Besides these six years, the conservatives led the government for over nineteen years, with Yitzhak Shamir, Ariel Sharon and Benjamin Netanyahu, who currently heads the administration. The Labour Party members were in command for less than a third of the last 36 years, with Peres, Rabin and Ehud Barak.

The program that brought Likud to power strongly opposed a social-democratic perspective and proposed radical privatization measures and the economy’s deregulation. It also supported the strengthening of the fight against the Palestinian resistance and an extensive settlement policy in the occupied territories after the 1967 war. The fusion of flags against the “oligarchy of kibbutzim and syndicalism” and in favor of the expansion of the Israeli border mobilized Jews who felt left out by the choices established until then.

The swing to the right is commonplace in the analysis of Israeli politics, but some prefer to identify more subtle changes. Yossi Beilin, who served as Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs and Justice in Labour Party governments, considers the idea that Israel is on track to hit more conservative positions a “simplification”. “Apart from occasional episodes, the two major parties converged to the center,” says Beilin. “The Likud eventually embraced the two-state solution to the Palestinian issue. The Labour Party began to defend the free market. “

NULL

NULL

Some facts corroborate his thesis. Between 1984-1990, when major liberal measures were adopted and broke the previous social-economic model, the two main parties were allied in government, and began switching off who held the prime minister post. The conservative discourse in favor of the two states solution, however, is a novelty of the present decade, and there are many doubts about it.

These doubts and resistances made Ariel Sharon, when the Israeli withdrawal from Gaza in 2005 was decided, turn away from his former party and found Kadima. He attracted to his company one of Havoda’s golden men, Shimon Peres, the current president of Israel. The distance between the two large Zionist political clusters may have actually been diminished. But the stroke suffered by the old general, in a coma since 2006, seems to have blown up some bridges between them.

The Current Administration

The current coalition government, elected in January, is leading the joint alliance between Likud and Yisrael Beiteinu, founded by Avigdor Lieberman, which comes from the far Zionist right. This coalition has 31 seats in the Knesset and occupies the key positions in the administration. The coalition expanded to include a new party, Yesh Atid, founded by Yair Lapid, which has 19 deputies and attracted many votes from the urban middle classes because of its speech against the privileges of the ultra-Orthodox religious, subsidized by the state and released from the obligation to serve in the army.

Mikhail Frunze/Opera Mundi

Yossi Beilin, former Deputy Minister of Foreign Relations and Justice in the Labour governments, dismisses right turn in politics

Another party that composes the extremist coalition-government is Habayit Hayehudi (Jewish Home), headed by businessman Naftali Bennett, which has 12 seats in the Knesset. Its platform is based the defense of Jewish settlements in the West Bank, the claim that much of this area is annexed to Israel and the rejection of any negotiations with the Palestinians on the division of Jerusalem.

The government completes its parliamentary base of 68 seats with the small Hatnuah, founded by Tzipi Livni, the current Minister of Justice. A secular party, more moderate than its allies, it leans towards a permanent settlement with the Palestinians and a social rights recovery policy.

The Labour Party members are the largest in opposition, with 15 deputies. To their right is the desiccated Kadima, which has only two MPs, but that was once an important breakaway from Likud, in the golden days when Sharon and Ehud Olmert (2006-2009) headed the country. On its left, there’s Meretz (six representatives in the Knesset), a party that inherited Mapam’s formation, and which combined, during the 40’s, the postulates of Zionism with a Marxist identity and the defense of socialism.

There are also two religious parties opposing the government, Shas and Yahadut Hatorah. The first, which has eleven deputies, represents the ultra-Orthodox, from Sephardic origin. The second, with seven members on the parliament, speaks for the orthodox fraction of the Ashkenazi. Both groups are out of the government because of the policies advocated by Lapid’s stream.

Another sector opposing Netanyahu is integrated by groups external to Zionism. The most important among these is Hadash, an Arab-Jewish composition directed by the Communist Party, with four deputies. Besides claiming the formula of two states, it proposes the recognition of Arab minority’s collective rights and the discontinuation of the liberal economy planning.

Two other parties of Arab origin also inhabit this slice of land. One that has secular characteristics is Balad, with three parliament members. And one other comes from Muslim affiliations, the United Arab List, with four representatives. Both claim the adoption of secular characteristics by the State of Israel, which should stop being characterized as Jewish.

Translation: Kelly Cristina Spinelli